Why Learning Philosophy Sucks

Published on 2023-10-21

For as long as there have been knowledge, there have been elitists of knowledge. You bet your ass Unga was telling the other cave-dwellers in 3000 B.C. that they weren't hunting mammoths the right way. "You plebeian rascals!" bunga'd Unga, "My art is infinitesimally more complicated than that! If you common folk want to learn how to really do it, you must reference paragraph four, tablet sixty-two of my stone tablet dissertation…"

Socrates, the father of western philosophy himself, carried on Unga's legacy. He said this about the practice of writing things down:

"...this invention will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it, because they will not practice their memory…you offer your pupils the appearance of wisdom, not true wisdom, for they will read many things without instruction and will therefore seem to know many things, when they are for the most part ignorant and hard to get along with, since they are not wise, but only appear wise."

Of course, we only know he said this because Plato, his trusty student, wrote it down in Phaedrus for us to enjoy. Writing:1 – Socrates:0.

Indeed, philosophy has a notorious reputation for harboring elitists. Some might say that this one of the reasons why learning philosophy, especially outside of higher education institutions, is a slow, difficult, and often boring task. It certainly seemed that way for me when I first started getting into philosophy– and although it got much better over time for me, the steep learning curve remains a significant barrier for most beginners.

The problem of philosophy education is further complicated by the discrepancy between how the general public perceives the subject and how academics conceive of philosophy. Many elitists would scoff at a layperson referring to their opinions as "my philosophy", as if they had just heard a cashier refer to their payment processings as "my theory of arithmetic." And this reaction is not totally unjustified– philosophy as it is practiced by ("real") philosophers today can be so complicated, technical, and rigorous, that it can resemble pure mathematics more than it resembles what laypeople have in mind when they hear "philosophy".

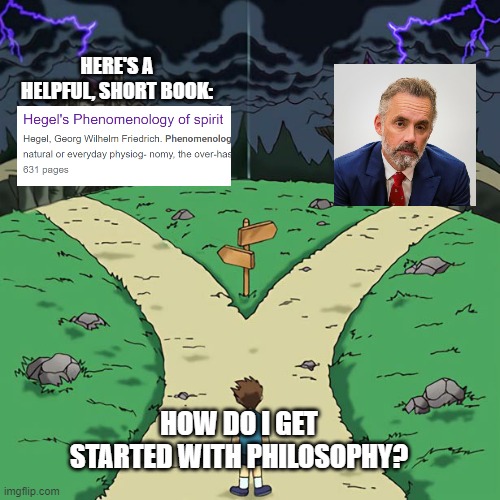

All in all, learning philosophy as a total beginner with only a curious mind to back oneself up is an uphill battle. Asking important philosophical questions like "What is the meaning of life?, "What is morality?", and "How do I live a good life?" will usually return three kinds of answers: a citation to a 700-page paper locked behind a paywall, a recommendation pointing to Andrew Tate/Joe Rogan/Jordan Peterson, and pop philosophy.

The first kind of answer has a lot of substance but is extremely inaccessible for beginners, as we have already discussed above. The second kind, what I will refer to as "pseudo-philosophy", is the opposite, being extremely accessible but having almost no substance of philosophical value. They only have the appearance of philosophy. This is where the public perception of philosophy comes into play, since the discrepancy between the public perception of philosophy and "real philosophy" determines what can even pass as pseudo-philosophy.

The final kind of answer, pop philosophy, is our point of interest. At first glance, pop philosophy seems to be a fine compromise between the former two extremes. In addition, the success of pop science (by science, I'm referring to the hard sciences here) and pop math, demonstrated by popular YouTube channels such as Kurzgesagt, 3Blue1Brown, and Vsauce, gives us hope that pop philosophy too can succeed in making philosophy accessible for a very wide audience. Alas, pop philosophy is not, in fact, that successful. There are several reasons for this, but I want to highlight just the three most significant ones.

First, philosophy as a subject is intrinsically more resistant to simplification compared to math or science. Things like the fundamental theorem of arithmetic or Newton's equation for gravitation are always true and demonstrable. Yes, that "always true and demonstrable" has many asterisk tacked on it, and we can go on and on about the definition of integers and operations, axioms, general relativity, etc., but their clarity and truthfulness is far greater than, say, Nietzsche's critique of religion, which cannot be well understood without also understanding its context, how Nietzsche developed it, how others responded to it, etc. In fact, many things in philosophy risk being totally misunderstood, sometimes even as the exact opposite of what it is, when simplified. On the other hand, pop math has no need to explain refutations to the fundamental theorem of arithmetic, since there are none (again, this may have asterisks, but observe that similar statements in philosophy would warrant entire chapters, not asteriks). Thus, pop philosophy cannot use the same kind of simplification that pop math and pop science uses; a different kind of simplification, or perhaps even an entirely different method, must be used to reach the popular audience.

The second reason why pop philosophy is unsuccessful is because philosophy is taken more personally compared to math or science. Basically no one gets upset at the fundamental theorem of arithmetic (they are only upset at the homework). For the hard sciences, the response can be more emotionally charged, such as in the case of evolutionary biology or cosmology, which can yield religious outrage, or in the case of neurobiology, which can yield political outrage. Nevertheless, most topics such as gravitation are taken with no emotional reservations, and even for controversial subjects like the ones mentioned above, the upset people are usually a minority. Philosophy, however, invites all kinds of charged responses. This is especially true because philosophy intersects with politics/culture/religion frequently (many parts of politics/culture/religion originate from philosophy), in which case, people's emotional commitment to politics/culture/religion, which they have cultivated for far longer and deeper, will often supersede their commitment to philosophy. This can influence experienced philosophy enthusiasts and professional philosophers as well, but casual beginners are even more vulnerable. If you read a philosophical argument and the only thoughts that pop into your mind are how they stand in relation to the political/cultural/religious commitments you already have, and you rush to come up with arguments to resolve any potential inconsistencies, as opposed to trying to understand and appreciate the argument for its own sake, learning philosophy becomes an inefficient, mentally draining journey.

Before I explain the final major reason why pop philosophy is unsuccessful, I want to bring attention to the question of what good pop philosophy content would look like. Good pop philosophy obviously needs to be entertaining, or at the very least, accessible– this is the "pop" part of pop philosophy. In the most successful pop math and pop science content, this is usually achieved by using an entertaining medium. For example, Kurzgesagt and 3Blue1Brown integrate their scripts into high quality animation videos. The visual art and fun easter eggs would have been sufficiently entertaining on their own, but they also enhance the scripts' message, allowing the whole package to be both entertaining and educational. This is also how the YouTube channel The School of Life, which produces some of YouTube's most popular videos on philosophers and philosophical ideas, makes their content entertaining. But despite The School of Life's effectiveness in making good entertainment, they are widely criticized for heavily biased presentations, lack of nuance, and sometimes even telling straight-up lies about philosophy and philosophers. This is where the other element of good pop philosophy comes into play: good pop philosophy should be, well, good philosophy. It should have a lot of nuance, be transparent with biases, have high standards for correct information, resort to simplifications only when necessary, and be clear when it does simplify.

This finally leads us to the third major reason why pop philosophy is unsuccessful: there is simply not enough good pop philosophy. Most philosophy-related content that is available to the public is either not entertaining or not good philosophy. The School of Life, as we talked about already, produces good entertainment but not good philosophy. The YouTube channel of professor Gregory B. Sadler has very good philosophy and is accessible, but is not really entertaining to the average person. Jordan Peterson, for whom some content creators like Philosophy Insights make videos about, is really just pseudo-philosophy, or, at best, very bad pop philosophy. Online encyclopedias such as the SEP, and its more accessible counterpart IEP, are very good philosophy, but would look closer to "700-page paper locked behind a paywall" than pop philosophy to a beginner.

There does exist some good pop philosophy: Philosophize This!, Wireless Philosophy, Overthink Podcast, Very Bad Wizards, The Partially Examined Life, etc. all do a good job of being both entertaining and being good philosophy. However, although I'm a huge fan of their work, I can't help but feel frustrated that good pop philosophy is not only much smaller and less popular compared to good pop math and good pop science, but more importantly, overshadowed by pseudo-philosophy and bad pop philosophy. People who are curious about science and math can use pop science and pop math as their starting point before making the jump to "real" science and math. But people who are curious about philosophy will most likely be exposed to pseudo-philosophy first, at which point making the jump to "real" philosophy is extremely difficult; after all, pseudo-philosophy is to astrology what philosophy is to astronomy. There must be more pop philosophy so that it can be used both as a starting point for new learners, and also as an intermediary jumping point for those who got exposed to pseudo-philosophy first.

All that to say, the world needs more good pop philosophy. Starting from next month, I plan on uploading a blog post at least once a month to tackle some "real" philosophy in an accessible, entertaining manner. At first, it will almost certainly be bad pop philosophy. But as time passes, I will get more experienced with writing, philosophy, and writing about philosophy; I have hope that it will turn into good pop philosophy.